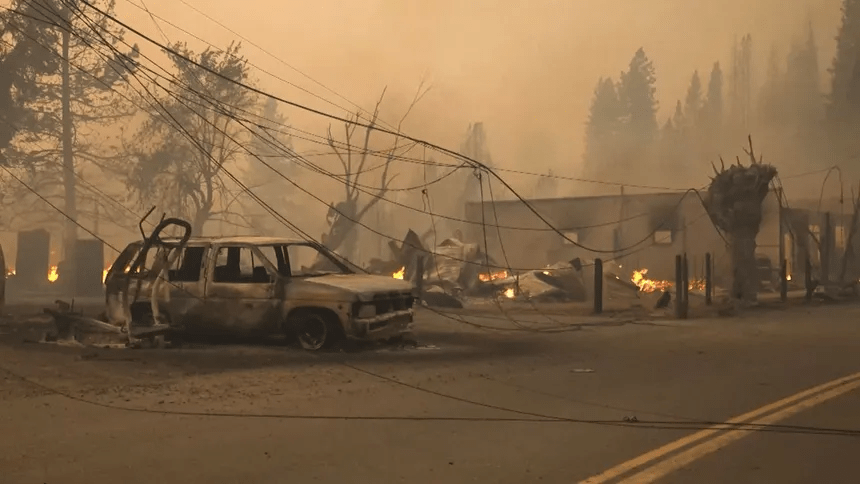

“Across this nation, increasingly destructive wildfires are posing ever-greater threats to human lives, livelihoods, and public safety.”

– ON FIRE: The Report of the Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission

The U.S. Forest Service has estimated that over 50 million acres of unhealthy national forest land is in danger of catastrophic wild fire. It would be far beyond the scope of this article to attempt to address the litany of policies and practices which have led us to this fiery precipice. But the fact is, for the foreseeable future at least, we can expect to watch as increasingly massive wildfires consume our forests and threaten rural communities.

When it comes to forest health, we’ve done nearly everything wrong. Over zealous fire suppression coupled with the demonization of the logging industry has led to overcrowded timber stands, massive fuel build up, insect infestations, and disease. Anti-American environmentalist’s have been very successful in blocking the utilization of our timber resources and locking up vast tracts of land in the name of “conservation”. Americans stood idly by as our timber industry collapsed under the weight of burdensome regulations and cheap imports.

Residents of once thriving rural communities understand the problem. Bumper stickers with the phrase,“LOG IT, GRAZE IT, OR WATCH IT BURN!” are often spotted in small town grocery store parking lots. Unfortunately, the underlying sentiment expressed by such simplistic memes, although containing a kernel of truth, betrays an ignorance of present realities. The fact is, the bulk of our forests are in such terrible condition that even if we increased grazing and logging a thousand percent, tens of millions of acres would still be at risk of catastrophic wildfire. It took longer than one generation to create the problem, and it will take several generations, and several methodologies, to solve it.

Before beginning my critique of current wildland fire policy, I should point out that fire has always been a natural component of our western landscapes. Numerous ecosystems and plant species are well adapted to periodic low-intensity fire. Some species actually require fire to propagate successfully. As a student of Natural Resources Management, and as a former Forest Service employee well acquainted with wildland fire and fire science, I understand that, when used appropriately, fire can be an effective management tool in maintaining and restoring ecosystem health. The good news is that many of our governing authorities are aware of the current situation, but the bad news is that these same authorities have not recognized how we got here, nor have they proposed adequate or effective long-term solutions.

A 340 page congressional report commissioned by the Biden administration in 2023 entitled, “ON FIRE: The Report of the Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission” identified the wildland fire crisis in the United States as, “urgent, severe, and far reaching’. Congress used this informative report as the basis for increasing funding for wildland fire management to a whopping $2 billion annually. While Congress has responded to the crisis by doubling the amount of money earmarked for Federal wildland fire management, such expenditures do not address the root causes of the problem or provide for a long term solution.

The authors of the Federal report admit that, “the drivers of the wildfire crisis are numerous and complex, and themselves are influenced by multiple forces and factors at all scales.” While the report goes out of its way to avoid playing the blame game, the solution(s) presented in the report, which at first glance appear to be multi-faceted and science based, really boil down to one primary strategy, which is to simply allow tens of millions of acres to burn.

On the flip side, those who think restoring forest health is simply a matter of increasing the amount of thinning, logging, or grazing, need to consider the facts. In the U.S. there has been a steady decline in the number of livestock being raised on both public and private land. In recent years the number of USDA grazing permitees on public forestland has declined by nearly 13%. This decline is a direct result of cheap imported beef and lamb, which precludes the need for American producers to graze more animals. This is especially true on public land in the western U.S. where livestock is increasingly exposed to unsustainable depredation due to the over abundance of large predators such as wolves and grizzly bears. The cost/benefit ratio is simply not favorable to livestock producers.

The same situation exists in the U.S. lumber industry which has to compete with $45 billion in imported forest products annually. According to the American Loggers Council, in just the last couple of years, over 50 U.S. lumber mills have closed and 10,000 timber industry jobs have been lost. There simply isn’t a demand for more logging here in the U.S. as long as cheap forest products are flooding the market from other nations. Federal land managers understand that without employing both of these productive fuels reduction methodologies, few options exist that can reduce the threat of catastrophic wildfire in a timely manner.

A 2017 University of Alaska study determined that current approaches to wildland fire mitigation, including mechanical fuels reduction and fire suppression, “are inadequate to rectify past management practices.” In 2014, the Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) concluded that, “In eastern Washington…at current treatment rates it would likely take 53 years to address the restoration need on federal lands alone.” In other words, hiring the manpower and spending the time and money on thinning programs and mechanical fuel reduction efforts is not as effective or cost efficient as simply lighting a match!

The concept of adding fire to fire depleted ecosystems has, by necessity, become the final solution for our National forests. Unplanned wild fires will be “managed” rather than aggressively suppressed. Prescribed fires (planned fires) will be used far more extensively and allowed to consume more acres. Novel concepts such as “Landscape Scale Burning” and “Cultural Burning” have become standard protocol. Of course, this short-sighted “burn it all” solution does nothing to reverse many of the factors that created the problem in the first place. According to current policies, forest resources will continue to be wasted (burned) rather than utilized for productive purposes.

And don’t think the Sierra Club wants it any different. Conservation organizations strongly support this new direction in forest “management” because it doesn’t involve logging or grazing, but returns America to the pre-columbian practices of the indigenous peoples who, in ages past, intentionally burned millions of acres every year. Department of Interior documents refer to this strategy as “Cultural burning”.

“Policy and management approaches to wildfire have focused primarily on resisting wildfire through fire suppression and on protecting forests through fuels reduction on federal lands. However, these approaches alone are inadequate to rectify past management practices or to address a new era of heightened wildfire activity in the West.”

-“Adapt to more wildfire in western North American forests as climate changes” – Univ. of Alaska 2017

A recent article in the Nevada Globe newspaper pointed out that, “Burning an average of more than six million acres a year… is now a standing order for the USFS, not only in California but across the nation.” Federal land managers now have the authority to enlarge wildland fires at their own discretion. This means that the number of acres consumed by wildland fire will increase dramatically over the coming years, with a corresponding increase in the threat to private property.

The article goes on to say that U.S. Forest Service chief Ryan Moore’s commitment to the Biden Administration “Burn Back Better” policy has caused a “firestorm among firefighters and Forest Service veterans nationwide.” The million acre Dixie fire in California (2021) resulted in over $13 billion in property damage and is a prime example of what can happen when fire managers intentionally enhance an “unplanned” fire. While the authorities blamed a downed powerline for initially sparking the fire, according to retired Forest Service and wildland fire expert Frank Carroll, fire bosses themselves were directly responsible for enhancing the fire far beyond what would have burned without their efforts. Over the 4 month life span of the fire, fire bosses ordered intentional, repeated, and aggressive “firing” operations which consumed an estimated 600,000 acres, or 60% of the total acreage burned. The fire destroyed 600 homes burning through several small communities.

Yes, we should increase productive alternatives such as grazing and logging on our nation’s public lands. But that won’t happen until we substantially reduce our reliance on cheap imports. Our goal should not be to keep prices down so that fixed income and low income people can afford to purchase cheap goods. Our goal should be to build prosperity and a sustainable future for all Americans. That won’t happen unless we reduce imports and control trade. President-elect Trump is right. The best way to control trade and insure long term prosperity is by setting tariffs on imported goods that we can, and should, be producing here at home for ourselves. Free trade was always a bad idea. Selectively controlling trade is the only way to insure that we can provide for the welfare of future generations, which includes properly managing our precious timber lands.

It’s going to take some time to right the ship. While Congress has doubled the wildland fire budget for 2025, merely throwing money at the problem is like using a hundred dollar bill to light a cigar. While it may make lawmakers look good, and Federal land managers feel useful, the results are likely to be negative for the economy, damaging for rural communities, and destructive for the environment. A change in direction is long overdue, but with Trump in office, anything is possible.

Sources for this article include:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/wildfire-crisis

https://www.nifc.gov/fire-information/nfn

https://www.doi.gov/wildlandfire/budget

https://www.fws.gov/story/2024-06/reducing-wildfire-risk-montana

“ON FIRE: The Report of the Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission” c. 9/2023, 340 pages. https://www.usda.gov/topics/disaster-resource-center/wildland-fire/commission

https://www.dnr.wa.gov/prescribedfire

https://www.dnr.wa.gov/StrategicFireProtection